China: Beyond Stimulus

Exploring consumer challenges, capital flight, and policy options for the world's second-largest economy

Hey crew,

I hope you’re all doing well.

I’ve been wanting to hold a webinar for you guys for some time now; so here it is.

Delving into the frameworks to turn macro analysis into actionable trade ideas.

If you’re not able to join any of the times suggested below for any particular reason please let me know.

China is the centre of focus for global macro, so let’s dive into the factors affecting the second-largest economy in the world.

In this report, we will review:

China’s deflation problem

Private sector debt burden

Capital markets weakness

Geopolitical headwinds

Stimulus isn’t Stimulating…

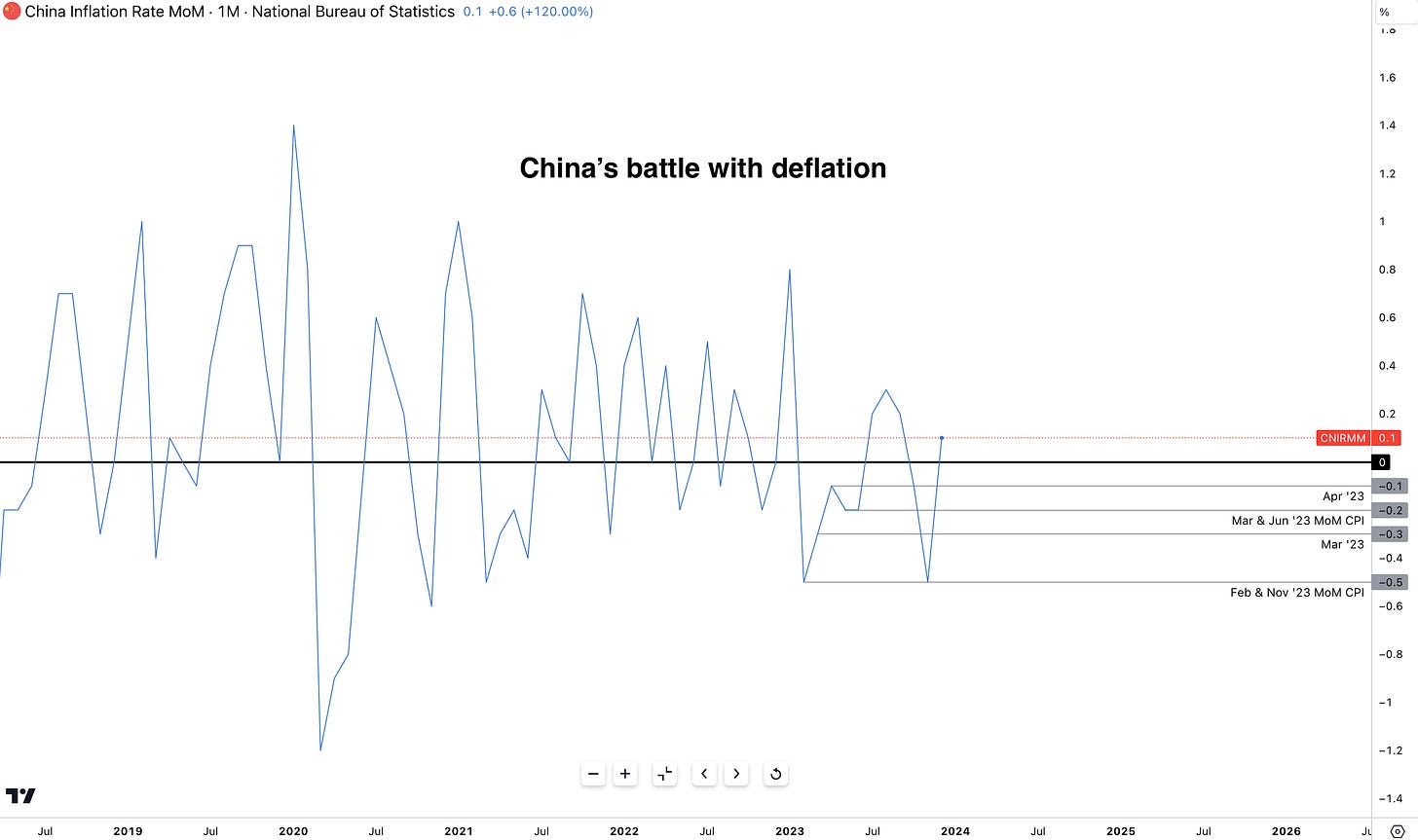

Since Covid-19 the PBOC, led by the Chinese government, has issued an unprecedented amount of fiscal stimulus and monetary easing, most of which has gone to waste as China has experienced six MoM readings of deflation out of the past 12 months.

China’s GDP expanded 5.2% in Q4 missing estimates of a 5.3% expansion, however, we did see an uptick in fixed asset investment YoY which clocked a 3.0% gain vs 2.9% estimate and a beat on China’s industrial production. Retail sales on the other hand soured the mood, ticking lower at 7.4% vs 8.0% consensus YoY (Dec).

Deflation’s deadly. There’s no way to sugarcoat it.

Whilst most may point to the positive effect of increased purchasing power as the price of goods decreases the second, third and fourth-order effects outweigh the increase in purchasing power.

China CPI MoM.

As seen in Figure 1, post-pandemic, China has struggled to spur inflation and domestic demand; exacerbated by a series of zero policy lockdowns to prevent the further spread of C-19 the second-largest economy found itself lacking a catalyst for growth.

Consumers Should Be The Focus

One of the imminent ripple effects of deflation is the sudden increase in the debt burden within the private sector. Now whilst a greater debt burden hurts both the public and private sectors, I’m going to focus first focus on the private sector, as within China non-financial private sector (aka consumers) is the driver of domestic demand and consumption.

Unlike the public sector, the non-financial private sector cannot expand its balance sheet the same way the public sector (government) can. This creates a fundamental difference in their financial behaviours, while the government can continue to expand its balance sheet through fiscal measures even under financial stress, the private sector (households & businesses) instead is forced to realise their debt burdens.

The public sector can expand its balance sheet through the act of issuing bonds, subsidies to businesses and nationalisation of the private sector. All of which Mainland China has done to boost its global profile. China's electric vehicle (EV) market serves as a prominent example, where government subsidies for consumers and manufacturers fostered rapid growth, catapulting China to the position of the world's largest EV market. These are just a few ways in which the public sector can expand its balance sheet to stimulate its domestic economy.

A key distinction between the public and non-financial private sectors lies in their balance sheet flexibility. While the government has the capacity to inflate its financial position through fiscal measures even under financial stress, businesses, with their access to capital markets, often have greater flexibility compared to households relying primarily on personal debt. Consequently, during periods of economic hardship, the private sector, particularly households, often bear the brunt of debt realisation, adjusting their financial positions and habits to pay down debts. The irony here is that the very part of the economy which drives consumption (households) is the same sector which feels the crunch first.

The result of this for consumers is, postponed/delayed purchases, declining consumer confidence, weak credit demand & a savings surplus. Other first-order effects can be seen in capital markets, on the investment side where lower consumer demand and consumption along with the overhang of deflation discourages investors from investing in domestic capital markets. This can be witnessed across China’s FDI flows, which recorded its first negative reading, meaning outflows, last year in Q3 ‘23.

Take a look at China’s equity market, the HSI (Hang Seng Index) in Figure 4 below.

Now observing closely, we can correlate the timing of the HSI peak with some geopolitical conflicts.

In January 2018 the HSI peaked at 33500.00, which was the same month the economic conflict between the Trump administration and China began. A constant exchange of economic bullets from both countries led corporations and investors to flee China’s capital markets as the uncertainty and risk associated with the trade war outweighed the risk/reward for investors seeking EM-sized returns from China. Since 2018 the Chinese index has not recovered, as the onslaught of tariffs, escalating geopolitical tensions with the US, Taiwan & its choice of allies have weighed in on investors’ investment decisions.

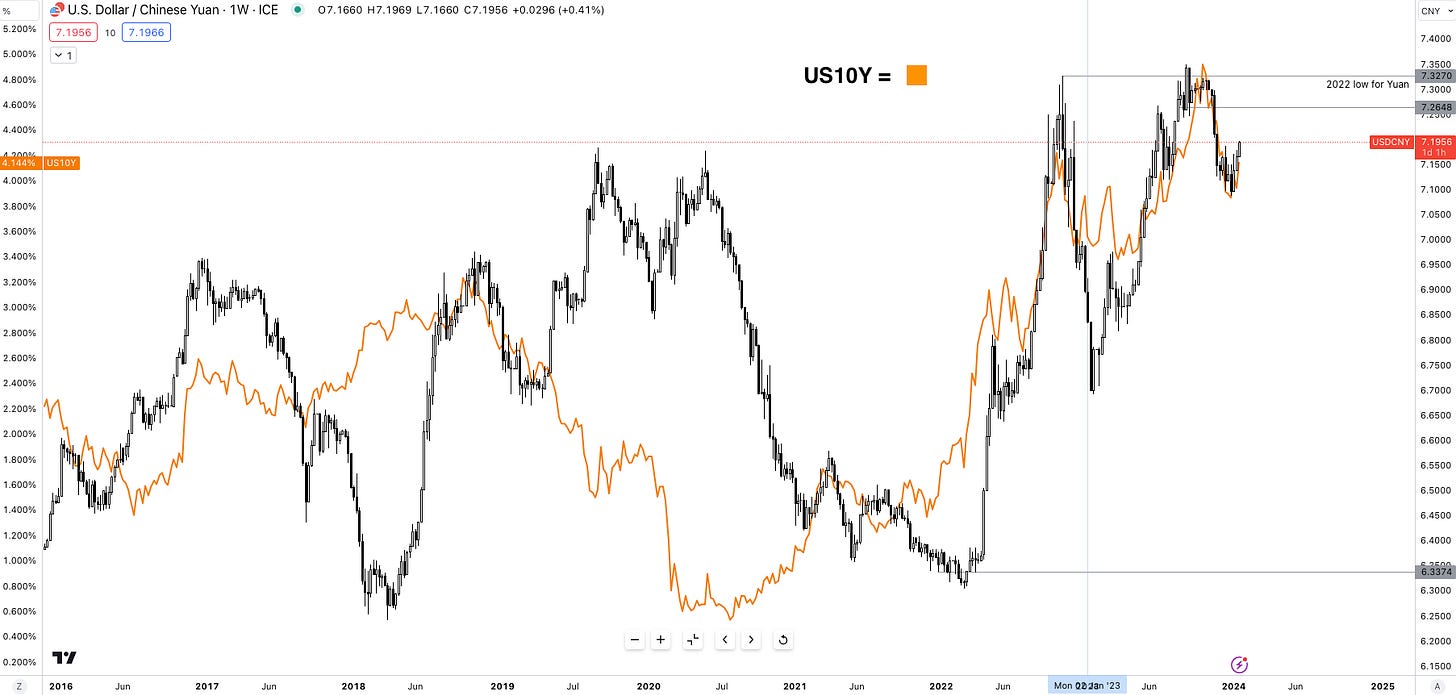

As I’ve broken down in several reports, interest rate differentials drive currency performance. Comparing the two 10y instruments further reiterates my point on how China lacks a certain appeal to its fixed-income markets; the recent Fed hike cycle has only accelerated the demise of Chinese debt and currency markets with the Yuan still trading within 2023 low territory.

As of Thursday 18th 2024, the CN 10Y yields 2.500%, and the US10Y is yielding 4.150% so a differential of (4.15%-2.5%=) 1.65%. The positive yield, accompanied by a strong dollar amidst geopolitical tensions makes capital allocation a rather simple choice when choosing between Chinese markets and U.S markets.

Figure 7 illustrates the clear negative correlation between US 10-year Treasury yields and the Renminbi (RMB). A rise in US sovereign yields tends to weaken the RMB. Therefore, for the RMB to appreciate, the People's Bank of China (PBOC) will likely need to either:

Increase its Loan Prime Rate (LPR): the key benchmark interest rate for lending in China. This would elevate borrowing costs and potentially attract capital inflows, bolstering the RMB.

Await a potential Federal Reserve interest rate cut: lower US yields could ease downward pressure on the RMB.

China's impact on global economic dynamics is undeniable. With a forecasted growth rate of 4.6% this year, a crucial question lies ahead: "Can China's engine rekindle global growth in the second half of 2024?"

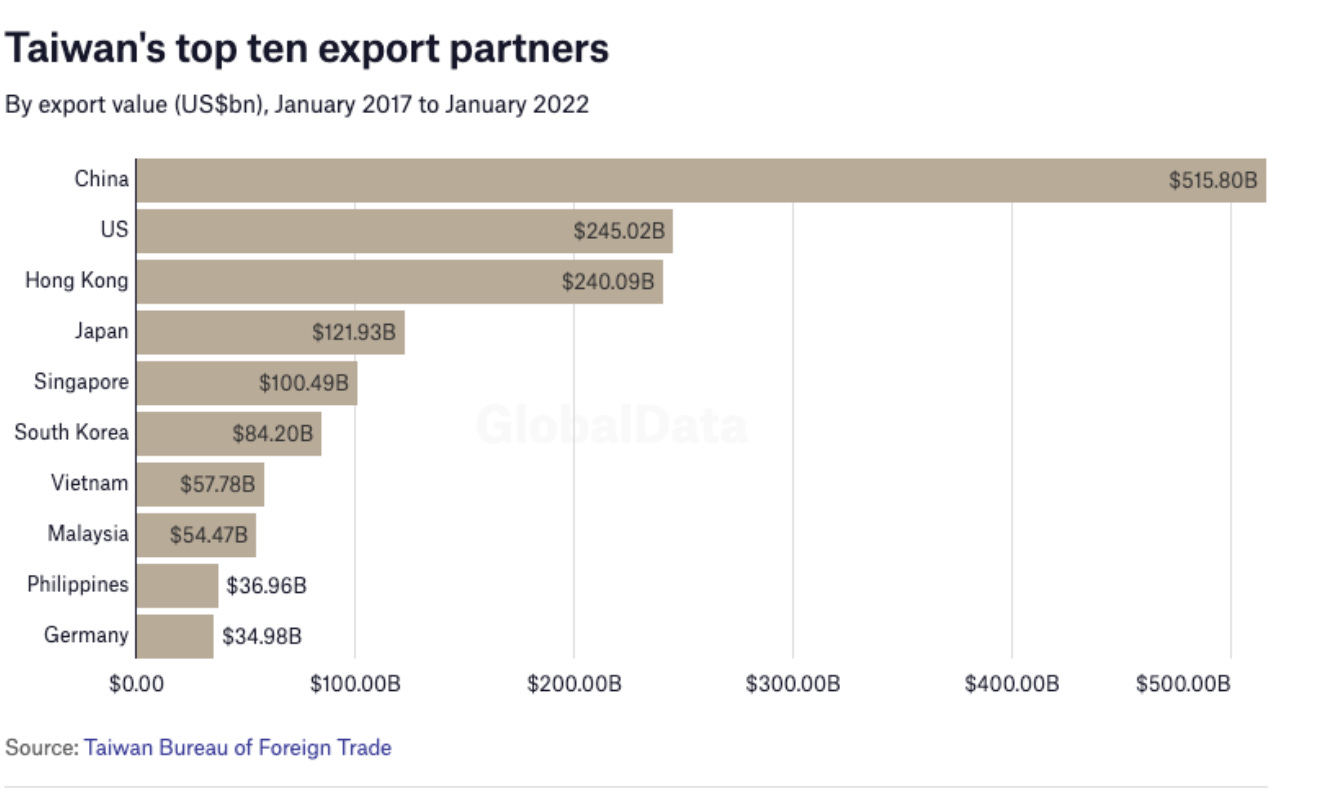

However, rising geopolitical tensions, particularly concerning China's aspirations to reinstate Taiwan back into its empire, cast a shadow on this prospect. The potential ramifications of Chinese aggression are amplified by China's significant reliance on Taiwanese goods, especially integrated circuits and semiconductors, vital for its technological advancement. Consequently, as the year unfolds. Ultimately, China’s foreign policy and its geopolitical manoeuvres will be the determining factor of its economic strength and therefore the global recovery, or its vulnerability.

That’s it for today crew, thanks for getting to the end.

I’ve had a few great conversations regarding articles released so keep it coming!

See you on the webinar.