The UK Trade Nobody Is Positioned For

Why disinflation, labour-market deterioration, and fiscal drag point to a deeper BoE cutting cycle that markets still underprice

The UK setup is drifting towards a major shift. It is setting itself up for a meaningful easing cycle in 2026, which has not yet been realised in the forward curve, and markets are barely acknowledging it. While the BoE continues to communicate caution, the underlying macro reality and the central bank’s own projections increasingly contradict that tone. This is not going to be a shock-driven downturn or a sudden collapse in activity (although we’re seeing some slowing). I view this move as a slower, grinding deterioration in the UK’s economic foundations, already visible in inflation dynamics, labour market data, growth composition, and fiscal policy. The result is a setup where multiple rate cuts are increasingly likely, yet UK rates markets remain priced for complacency, particularly at the front end and in terminal rate expectations.

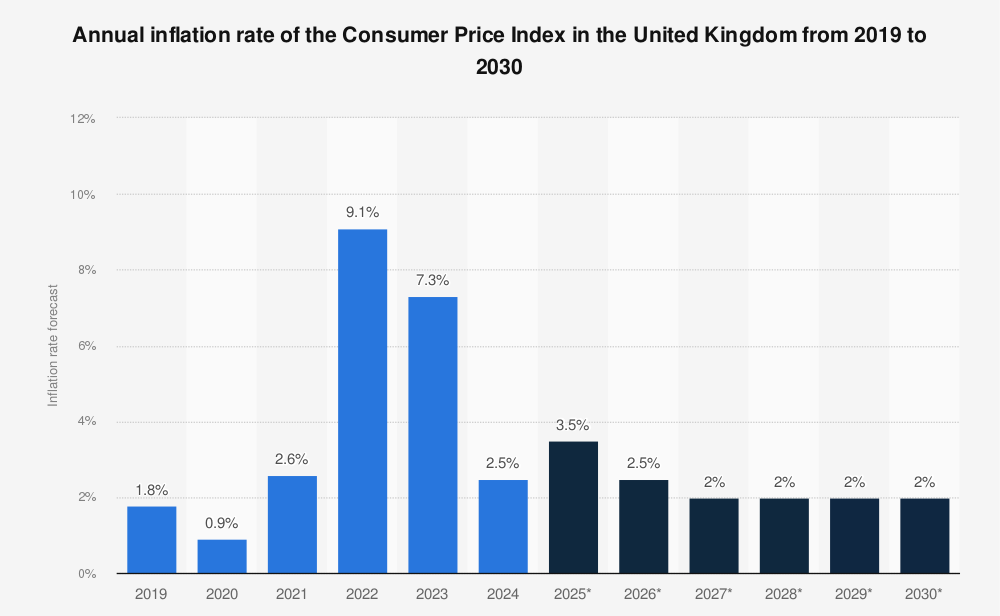

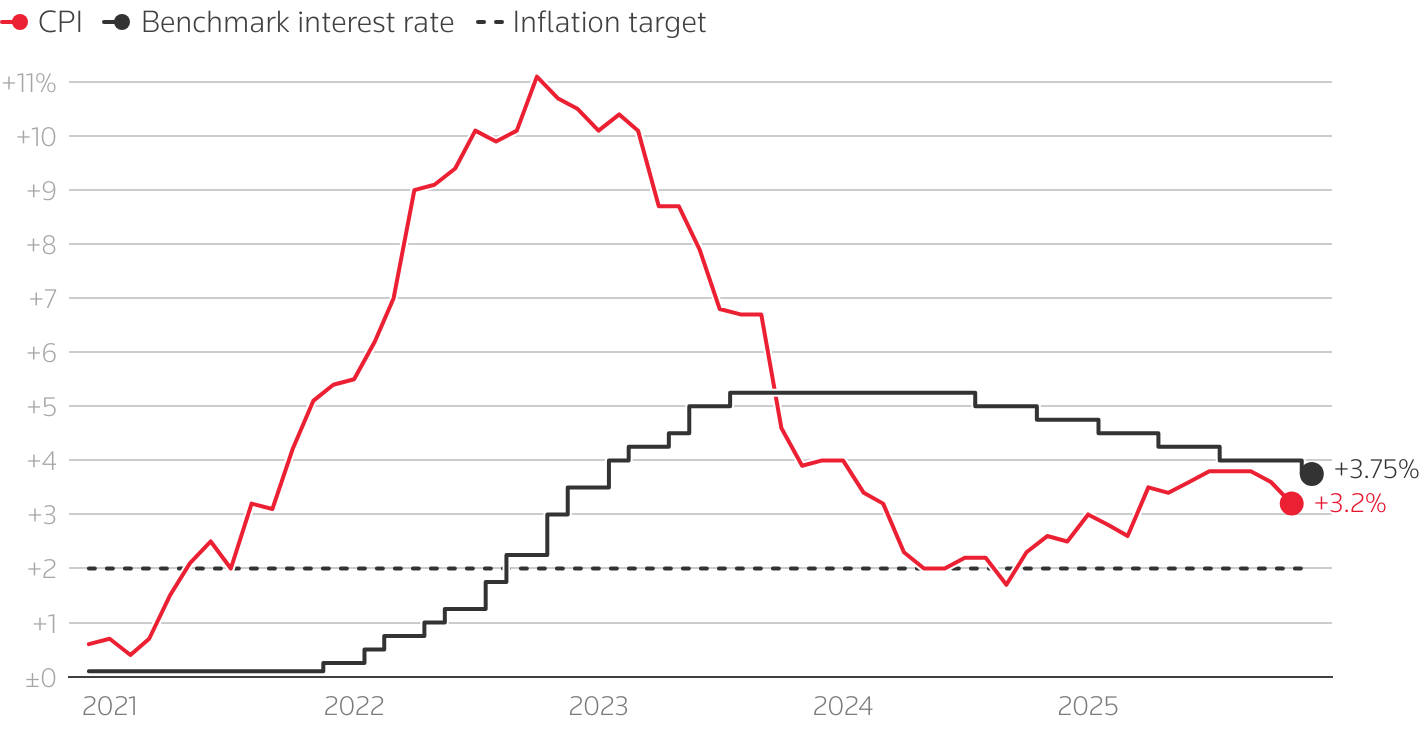

The BoE’s messaging still leans heavily on residual inflation risk and the need for patience, but OBR forecasts tell a different story. Inflation is projected to sit around 3% in early 2026, ease towards roughly 2.5% by year end, and fall below target sometime in 2027. That path does not justify policy remaining meaningfully restrictive (as it is), especially in an economy with weak trend growth and deteriorating labour-market conditions. Historically, when central-bank forecasts begin to sketch a clear disinflationary trajectory, the policy stance tends to follow with a lag. The UK looks increasingly close to that inflection point.

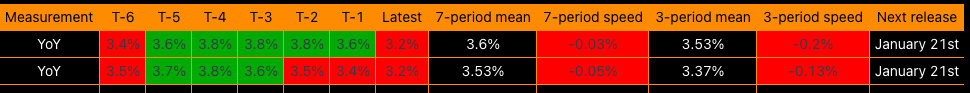

More important than the level of inflation is its momentum, and here the picture has improved materially. Inflation is smoothing out rather than re-accelerating. Services inflation is losing steam, goods inflation is no longer generating upside surprises, and there is no sign of a renewed inflation impulse of the type that previously forced the BoE to stay hawkish. This mirrors the recent US experience, where inflation rotated from a “sticky” narrative to a more controlled deceleration. In the UK’s case, that shift removes one of the last credible arguments for maintaining a highly restrictive stance. Both core and headline CPI have negative 3 and 7 month speed, with recent prints below both the 3 and 7 month averages, as inflation continues to become less of an issue... but by no means am I saying they have victory over inflation.

(Top = Headline CPI. Bottom = Core CPI)

Wage dynamics reinforce this point. Wage growth is easing from elevated levels and, crucially, is no longer accelerating in a way that threatens to re-ignite inflation. The feared wage price spiral has not materialised. Instead, wage growth appears to be responding to softer labour demand, rising slack, and weaker hiring intentions. As with inflation, the direction of travel matters more than the absolute level, and on that front the signal is clearly turning more benign.

The labour market itself is now the most important macro signal for the MPC. Unemployment has drifted above 5%, vacancies continue to fall, and hiring momentum is slowing across much of the private sector. These are not noisy indicators. Historically, once unemployment begins to rise in a sustained way, central banks shift their focus away from fine-tuning inflation outcomes and towards recession-risk management. The BoE is unlikely to be different. Faced with a weakening labour market, policymakers tend to prioritise cushioning the downturn rather than ensuring inflation is pinned perfectly at target.

(Top = Nominal GDP. Middle = Unemployment rate. Bottom = Job vacancies)

The decline in vacancies and hiring intentions suggests that labour demand is rolling over rather than merely cooling. This is the stage of the cycle where central banks often end up reacting more forcefully than markets expect, particularly if the deterioration continues over several months. Importantly, UK rates markets have not meaningfully repriced this risk yet. Only a limited number of cuts are priced, leaving significant asymmetry if labour data continues to weaken.

At the same time, higher rates, rising wage costs, and increased taxation are beginning to expose fragile corporate balance sheets. So-called zombie firms are starting to fail because financial conditions have remained tight for too long (although with fair reason). Taxes have played a major role here. Higher National Insurance, increases in the minimum wage, and broader tax pressures have all contributed to a quiet but powerful tightening of conditions for businesses. This form of tightening is particularly damaging because it is structural rather than cyclical.

Looking ahead, the near-term labour outlook is relatively straightforward. Job losses are likely to rise, unemployment should continue to drift higher, and inflation is set to tick lower. Yet markets are still pricing only a modest easing cycle of 2 cuts this year. That disconnect creates a clear vulnerability. If labour market weakness becomes more pronounced through the first half of the year, the repricing in rates is likely to be abrupt rather than gradual.

Growth provides little reason for optimism. UK trend growth appears capped around 1-1.2%, constrained by weak productivity, unfavourable demographics, and chronically low investment. More concerning is the composition of growth. Increasingly, whatever growth the UK does generate is driven by the public sector rather than private investment. That is not a sustainable engine of expansion and tends to coincide with lower productivity and weaker long-term potential.

Business investment remains well below pre-COVID levels and shows little sign of a durable recovery. Fiscal policy is not helping. If anything, it is acting as a drag. Rather than incentivising private investment, the current policy mix is weighing on corporate profitability and confidence. At some point, stimulus becomes unavoidable, and monetary policy is the most immediate lever available. Lower rates are not a panacea, but they are a necessary condition for stabilising investment and preventing a deeper slowdown.

Fiscal policy has turned from support into drag. Since Labour’s election win, the direction of travel has been clear: higher taxes, higher labour costs, and a tighter fiscal stance in growth terms. This represents a pro-cyclical tightening into an already weak economy. In such an environment, monetary policy is typically forced to do more of the heavy lifting. That argues for a faster and deeper easing cycle than markets currently expect.

Even after the initial cuts, policy is likely to remain restrictive in real terms, and has been for some time. With inflation easing along the Bank’s projected path, real rates would stay positive unless nominal rates are reduced more aggressively. This lowers the bar for additional cuts and increases the risk that the BoE ends up doing too little rather than too much if it moves cautiously.

All of this points toward a shift in the MPC’s priorities. As the cycle matures, the focus is likely to move decisively toward managing recession risk rather than guarding against residual inflation threats. Central banks rarely wait for full confirmation in labour data before acting, and the UK is now close to the point where pre-emptive easing becomes the rational choice.

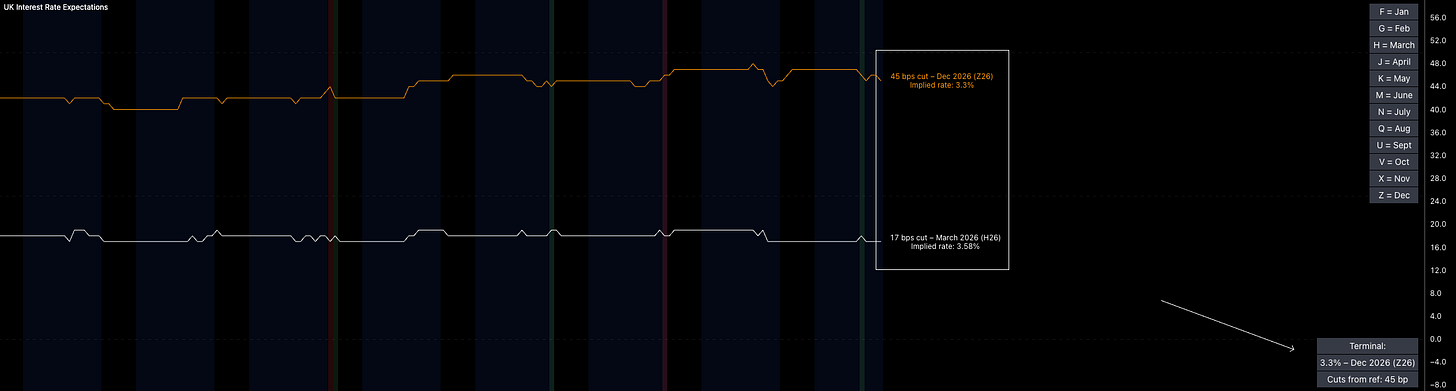

Despite this, markets continue to underprice UK easing. Much of the global macro focus remains on the US, leaving the UK under-analysed and under-positioned. A base case of 75bp of cuts in 2026 looks reasonable in my take, with upside risk toward 100bp if unemployment continues to rise through the first half of the year (likely realised in market pricing by H2). The most powerful part of the repricing is likely to occur in the reassessment of the terminal rate, which remains too high given the UK’s structural growth constraints. The market is only pricing around 2 cuts this year with the terminal rate of 3.25% to be hit by year-end.

The divergence between the UK and the US reinforces this view. The UK faces weaker growth, poorer productivity, rising unemployment, and increasing fiscal drag. The US, by contrast, continues to benefit from stronger private investment, better productivity dynamics, and a more supportive fiscal backdrop. Even if both central banks ease, the UK is likely to underperform economically, and rates should reflect that divergence. This gap is driven by fundamentals, not by temporary policy differences.

In short, the UK easing story is a slow-burn macro mispricing. Inflation is easing, labour is weakening, growth is capped, and fiscal policy is restrictive. The BoE will respond in my view. Markets have not yet adjusted to that reality, and that gap is where the opportunity lies.

The cleanest way to express this view is via the UK front end, because that is where the repricing of both the number of cuts and the terminal rate should show up most directly. Conceptually, being long SONIA Dec-26 captures the point in the curve where growth fear can become most market-moving, especially if labour-market weakness continues to build into mid-year and the BoE starts to pivot more decisively. The appeal is that if the market moves from pricing a couple of cuts to a proper easing cycle, Dec-26 is a natural anchor point where those expectations concentrate. Timing-wise, the biggest convexity likely comes if there is a clearer catalyst around late spring into summer (May-June) or into the second half, when the accumulation of softer jobs data typically forces the market to stop hand-waving and start repricing.

I want to make it clear that I am unable to express the idea above due to asset limitations on my trading accounts. However, the trade below will be taken and added to the macro trade tracker.

A UK curve trade that matches this macro framing is a long UK 2s30s steepener. The logic is that the 2y is the cleanest instrument for repricing the depth and speed of cuts, and especially the shift in terminal expectations, while the 30y is less about near-term growth optimism and more exposed to term premium and fiscal credibility. In other words, even if the BoE cuts, the long end does not have to rally in the same way if investors demand extra compensation for fiscal drag, higher supply, and longer-run structural issues.

That is the key difference vs the US, where the long end can more easily reflect a higher growth, higher productivity narrative. In the UK, the long end is more likely to be anchored by supply and fiscal concerns rather than a bullish growth regime, which makes 2s30s a cleaner way to express front-end rallies on cuts while the long end stays relatively heavy. The trade in real terms is: buy 2Y Gilts and sell 30y Gilts. Profit as the yield spread widens (30Y yield rises relative to 2Y yield). For simplicity, I will be adding the trade as “UK 2s30s steepener” to the trade sheet.

This is how I view the setup for the UK 2s30s steepener, targeting 2% and invalidating at 1.3%:

So taken together, the trade framework is consistent: the front end is where the market is most wrong on the easing cycle, the UK vs US front-end spread is where the market is most wrong on the relative divergence, and 2s30s is where you express the view that cuts arrive without a great growth backdrop, leaving the long end more constrained by term premium and fiscal dynamics.

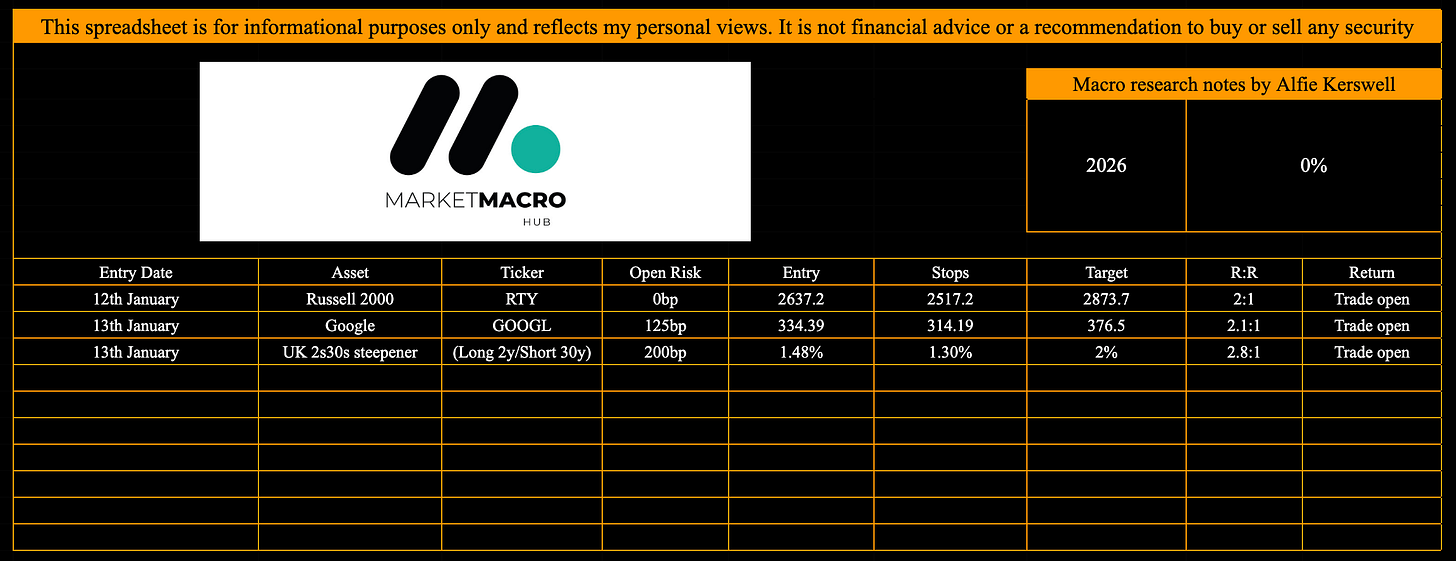

This is what the trade sheet looks like now:

Have a good one!

Top read Alfie

Is the Sonia the U.K. equivalent to the US SOFR ,and to calculate the BOE future cuts do you subtract , for example the 3 month futures Sonia contract from 100 to get the predicted basis points like the SOFR

Thanks

Similar thoughts, but was wondering if the trade should be done via 2s10s steepen instead of 2s30s steepen. DMO has been issuing more front-end gilts compared to the 30s gilts. So wouldn't doing 2s30s have a higher chance of flattening compared to 2s10s?