Silicon Valley Bank's Systematic Failure...

Deconstructing the largest bank failure since 2008 & the ripple effect

Hey guys,

Currently seated at my desk writing this as I wonder what on earth has happened the past seven days. Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and now Credit Suisse causing a frenzy in markets.

We’ll get into that later on, but for now, here’s a sneak peak of one of my favourite chapters in the Four Foundations Of Macro FX:

We’re launching March 31st, but I’ve got to let you know.

This isn’t for a newbie trader or macro analyst.

It’s far too advanced.

This is for traders with 2+ years experience, looking to bridge their gap in knowledge.

So, if you want to learn faster than 90% of traders in less than 90% of the time, I’ll see you at the launch.

Anyways, we’ve got a banking crisis to talk about.

Lend me your attention from here on out.

What Happened To Silicon Valley?

Let’s get straight into it.

Probably thinking where do I start right?

Let’s start with the mechanics of how a bank functions before assessing SVB’s systematic failure.

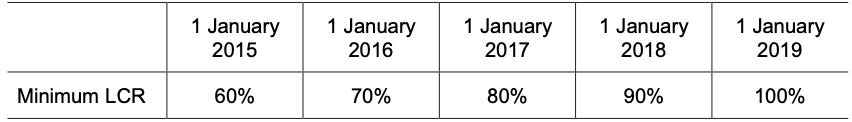

Post the GFC crisis in 2008, a regulation was put in place which strictly told banks how much of their holdings should qualify as HQLA, aka, high-quality liquid assets. The ratio is called the liquidity coverage ratio, which needs to be 100%. That means you need to have enough liquid assets on your books to meet stressed outflows of deposits over a 30-day period.

Following?

Good. Now, this is what the HQLA regulation looks like.

Banks considered to be systematically important banks, come under the LCR regulation, meaning any bank/financial institution with over $250B in assets must be stress tested regularly to ensure they have viable liquidity to withstand a period of extreme outflow and abide by these rules to the tee.

Somehow, SVB, managed to slip under this regulation, they only had $208B in assets, meaning SVB didn’t have to comply with these tight and strict regulations where they would go under stress tests on their interest rate risk.

So, Silicon Valley Bank, in line with the HQLA requirements, decided to purchase a tonne of government bonds and 10-year duration MBS securities (mortgage-backed securities). But here’s the issue.

SVB used short-term client deposits, as its clients required regular access to their cash, to invest in longer-term fixed-rate assets, being U.S Treasuries but mainly 10-year MBS securities.

Take a look at their balance sheet. Credit to my favourite Friday Pod, All In Podcast for the visual.

Here’s where things get sticky for them.

Say you buy a government bond which is yielding roughly 2% annually, and interest rates rise to 4-5%, new bond issuances will now be yielding substantially higher interest rates than the original bond yielding 2%. So, say these newly issued gov bonds now yield 5%, in order for the first bond to match the rates that new bonds are being issued, those bonds have to trade at a discount of roughly 25% in order to match the new rate of 5%.

That’s where SVB were caught up. In their hold-to-maturity account, SVB were holding onto a huge amount of MBS securities and Treasuries that were trading at a discount, an unrealised loss for the bank. Now that’s not at all new for banks, all large banks, JPM, Wells Fargo, Barclays, Citi Bank and many more all hold onto bonds which are currently in losses, but what these banks do that SVB didn’t is they hedge their risk with interest rate swaps.

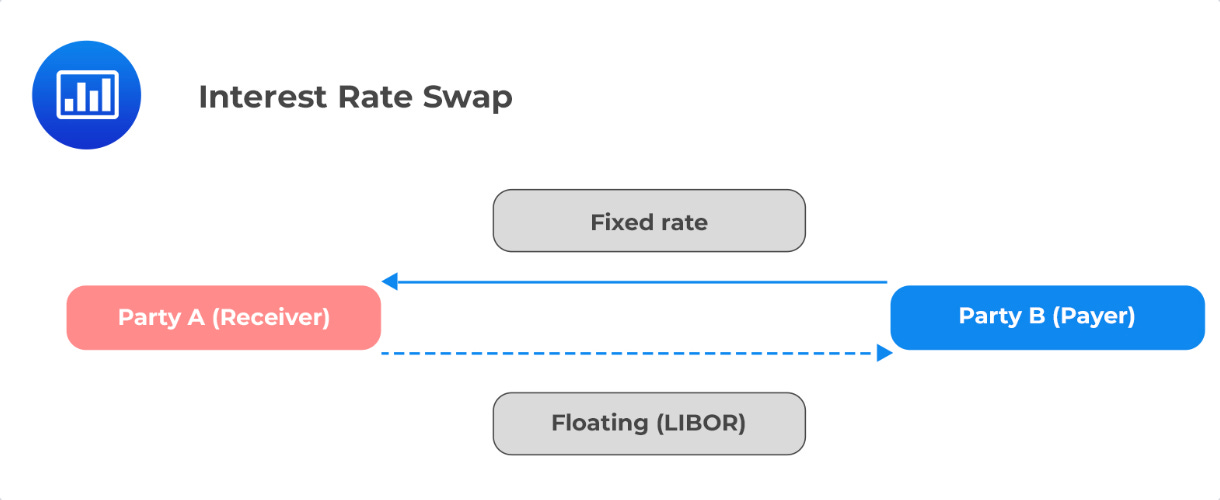

Here’s what this means.

The fixed-rate going to party A, is also known as the swap rate, the rate demanded by the receiver of a swap to exchange the floating rate, and the floating (LIBOR) is the floating interest rate over that time the bank would receive.

How does it work?

Good question; here’s how.

When a bank buys a bond yielding 2%, to hedge the risk of interest rates in the event rates rise, they enter an interest rate swap where the bank pays a fixed interest rate and receives the floating interest rate in return, so although their bond portfolio holdings may be underwater, they’re in the money, or in the green with these interest rate swaps. Practically offsetting risk from interest rates, so let’s say you had 10y Treasuries yielding 1.5% and now 10y Treasuries are yielding 3.5% your gain is that differential of 2%.

SVB decided not to hedge those interest rate risks, and that was a systematic error. As a result, they were forced to crystallise those bonds which were underwater, in a loss. Result? Large losses led to a collapse.

The part which triggered the run on the bank was the ‘$26B available for sale securities’. The issue here that caused fear is that SVB, with their current balance sheet, would have only been able to redeem roughly 25% of all deposits since they had $26B available for sale. Once word got out of how illiquid SVB were, VCs began advising their portfolio companies to withdraw deposits from SVB which ensued the bank run.

As you know, once fear settles in the market, it’s impossible to stop, so in a rush to save deposits $1m in deposits were withdrawn from the bank every second last Friday forcing the FDIC and the Fed to step in.

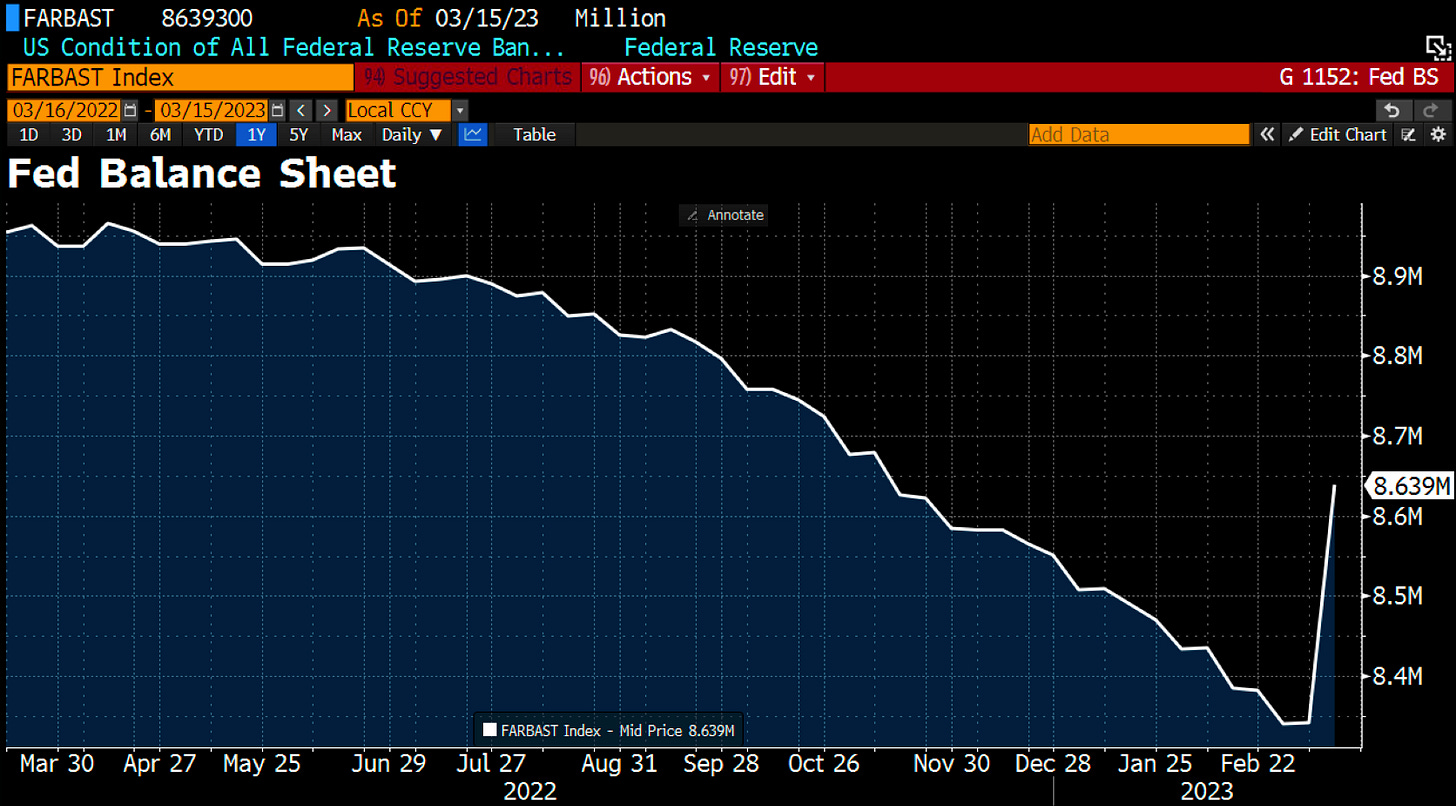

Here’s how the Fed’s balance sheet has changed over the past week.

$297B was added to the Fed’s balance sheet.

The Fed began QT back in June of 2022, the Fed began rolling off $30B in Treasuries and $17.5B in MBS securities; they later stepped that up to $60B per month. So c$500B was removed from the Fed’s balance sheet from June through to March ‘23, and in 1 week the majority of QT has been reversed as the Fed opened an emerging lending program to support the banking system.

Since the Fed’s announcement on Sunday, $11.9B has been borrowed by banks through the Bank Term Funding Program, meaning banks can take one-year loans under favourable terms in exchange for high-quality collateral. A further $153B was drawn from the Fed through the discount window, providing loans of up to 90 days to financial institutions, and lastly, we saw an additional $142.8B in bridge loans the Fed made to support institutions.

Where do we go from here?

I’ll be analysing the ripple effect as we go on, but in the immediate scenario, I see further capital flows from smaller non-systematically important banks to the large systematically-important banks as businesses evaluate the solvency of their banks and the risk of this happening which could cause further stress tests and bank runs in the U.S.

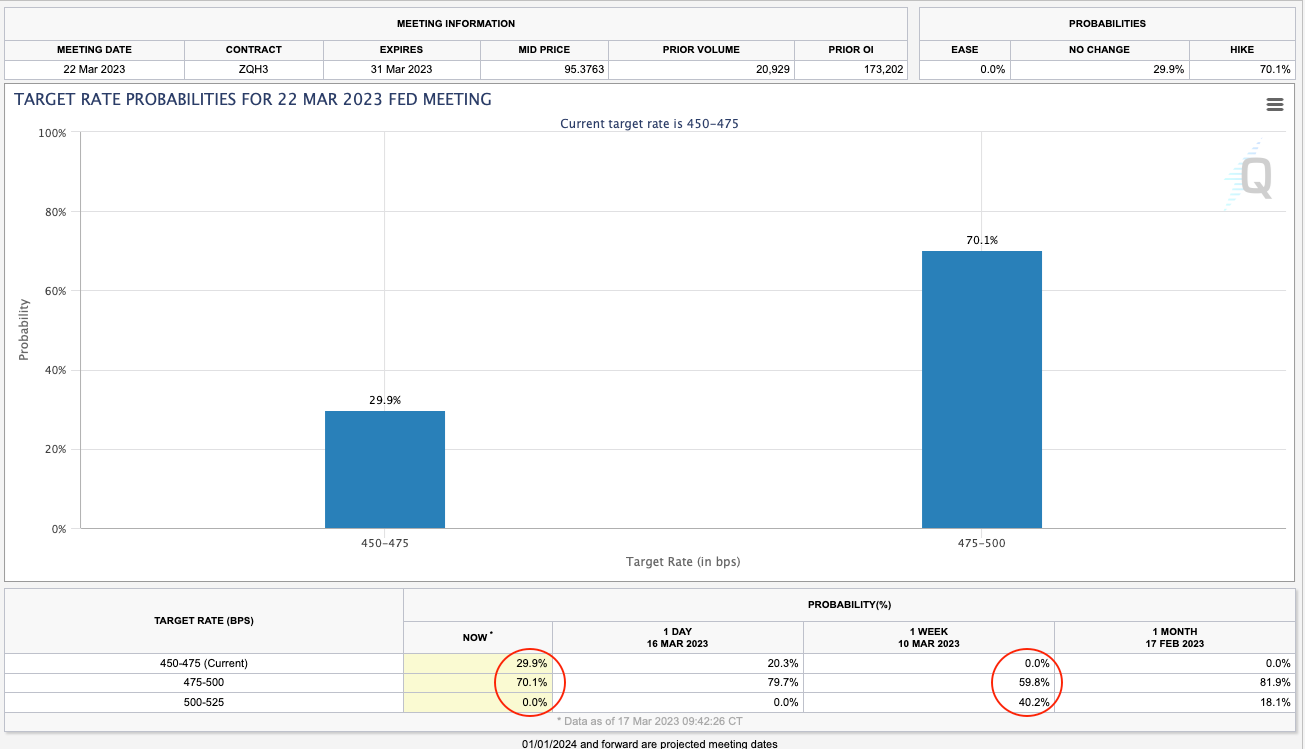

Looking further the FOMC meet in 5 days, and the markets expect the Fed to hike only by 25bps, with some banks calling for either a pause or a cut!

I think the Fed after evaluating recent events may choose to hike with only 25bps, however, I’ve got a 40% probability that the Fed will look at this as an independent event of a bank mismanaging its risk and hike by 50bps, although that is looking less likely at the minute.

Anyways, I’ll be covering the situation as we develop, that’s the end of this week’s post.

Nice 👍

Thanks for the newsletter .