Primer: The Ladder of Derivatives, From Simplicity to Sophistication

From Vanilla to Exotic: The Derivatives Ladder

Hey everyone,

Focus is a skill, and like any skill, it sharpens with practice.

The best trades, and the best days, come from that centered state of mind.

Let’s begin.

I’m going to break this primer down as simple as possible, so that the layman (like myself) can understand it. There is truly nothing worse than reading primer’s that are full of jargon.

Understanding the derivatives ladder

Derivatives form a ladder of increasing precision and complexity, with each rung unlocking a new way to express views, hedge risks, and shape payoffs.

Forwards are the simplest bilateral form of a derivative. They are private, over-the-counter agreements to exchange an asset at a future date for a fixed price agreed today. Unlike futures, they are not standardised or centrally cleared, which means they embed counterparty risk but offer flexibility in tailoring size, maturity, and settlement terms. Corporates often use them in FX or commodities to lock in costs or revenues, while investors may use them to gain tailored exposures where listed contracts are too rigid. Forwards thus represent the building block upon which the exchange traded futures market was developed.

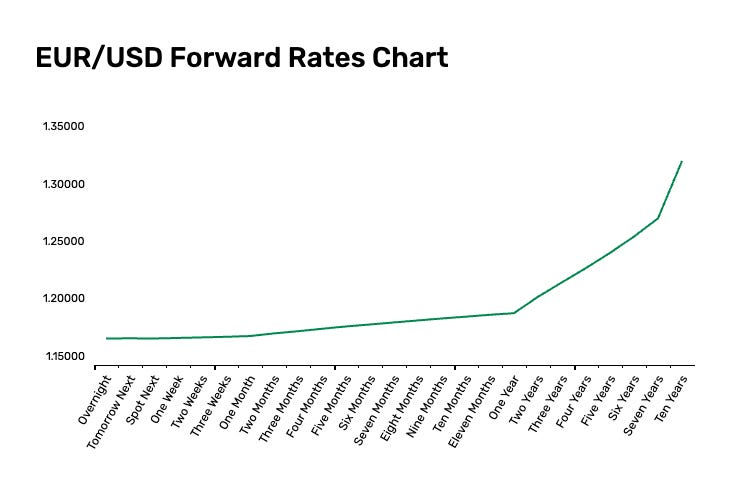

Forwards also remind us that derivatives were born from real world commercial needs. Whether it was farmers fixing crop prices or airlines hedging jet fuel, the purpose was always risk transfer before it was speculation. In today’s markets, forwards remain the quiet backbone of FX and commodities, a reminder that beneath the abstractions of swaps and exotics lies a simple human instinct: lock in certainty in an uncertain world. You can see how uncertainty in one currency gets priced into forward rates:

Futures represent the next rung. They are standardised contracts, centrally cleared with tight spreads, low commissions, and high leverage. Hedge funds use them for beta transfer, dialing market exposure up or down quickly through equity index futures, FX, or commodities. They also provide efficient access to duration, with Treasury, Bund, or SOFR futures allowing managers to add or subtract DV01 without disturbing cash bond holdings.

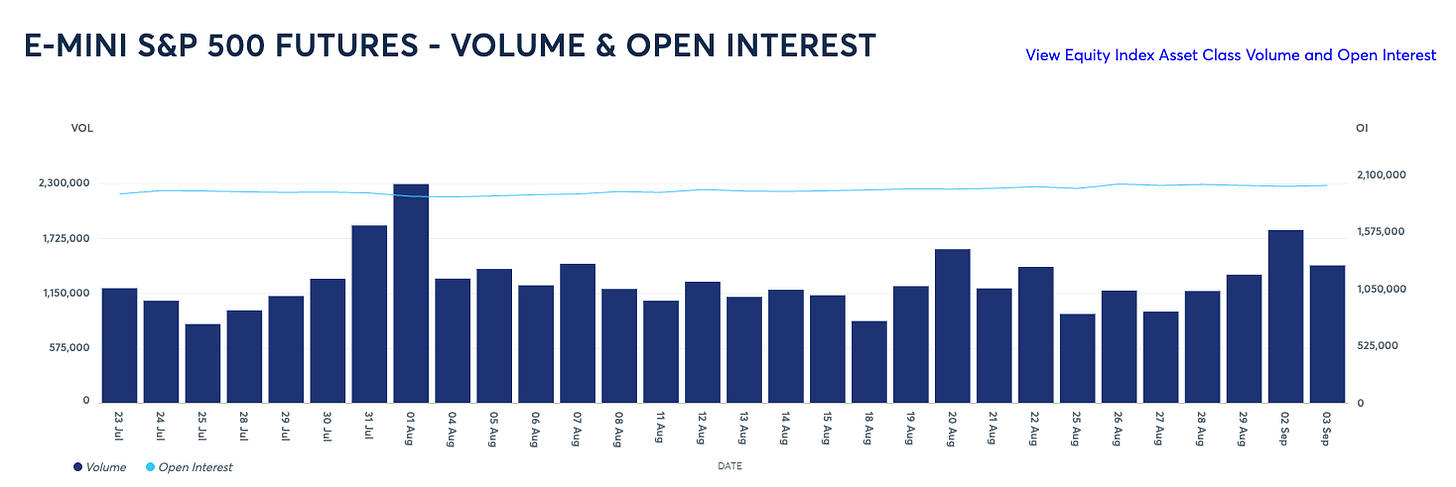

What makes futures so powerful is their role as the purest expression of market beta. They are the workhorse of asset allocation, allowing managers to swing exposures without touching the cash portfolio. This is why asset managers benchmark against them, CTAs build models on them, and macro traders constantly lean on them because they are the cleanest, most liquid instruments in the game which you can see below in S&P 500 futures:

Options come next, introducing convexity and volatility views that allow investors to control path risk and pay for asymmetry. Options transform risk into shape. They allow traders to define exactly how they want to participate in a move that is capped, floored, asymmetric, or leveraged. This ability to sculpt payoffs explains why they sit at the center of volatility markets and why the language of convexity, skew, and implied vol has become as important as the traditional language of rates and spreads. This is visible in the S&P 500 volatility skew, where out-of-the-money puts command higher implied vol than calls, a structural premium that reflects persistent hedging demand:

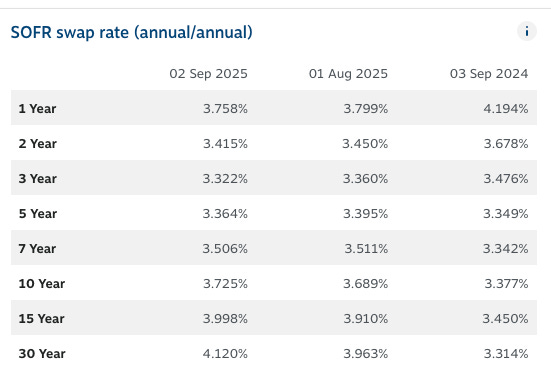

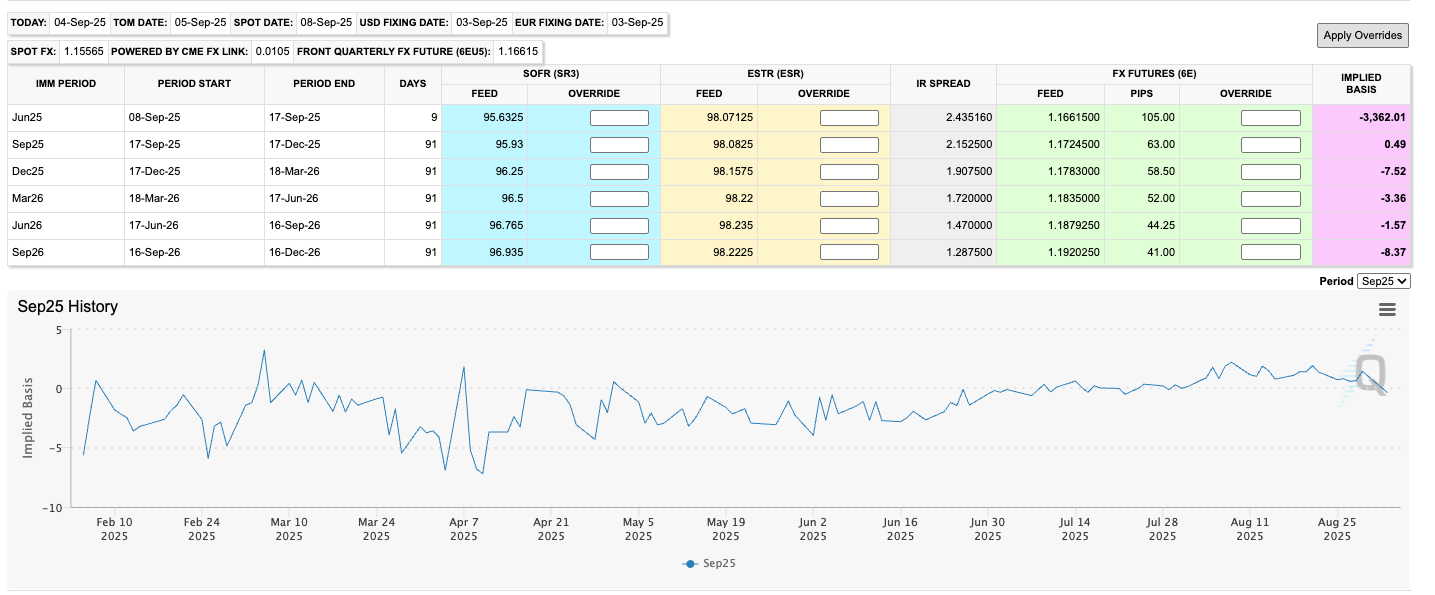

Swaps occupy the fourth rung, providing bespoke rate, credit, and funding exposures that enable investors to structure curve, basis, and carry with surgical precision. Swaps are where derivatives start to feel like engineering. They aren’t just tools for trading direction but for trading relationships — the slope of the yield curve, the basis between funding markets, or the spread between credit indices. They are the plumbing behind everything from mortgage markets to sovereign debt management, invisible to most, yet essential to how the system functions day to day. One way to see this plumbing in action is through the SOFR swap curve, where traders use spreads between maturities (like 2s10s) to express curve views or hedge balance-sheet risk:

At the top are exotics and hybrids, where highly targeted convexity in rates, volatility, or correlation can be engineered, though these instruments are powerful, path-dependent, and operationally demanding. The art lies in matching the instrument to the objective, horizon, liquidity, and risk budget, while avoiding the common mistake of buying unnecessary complexity or, conversely, failing to recognise when a vanilla instrument cannot replicate the payoff you truly need.

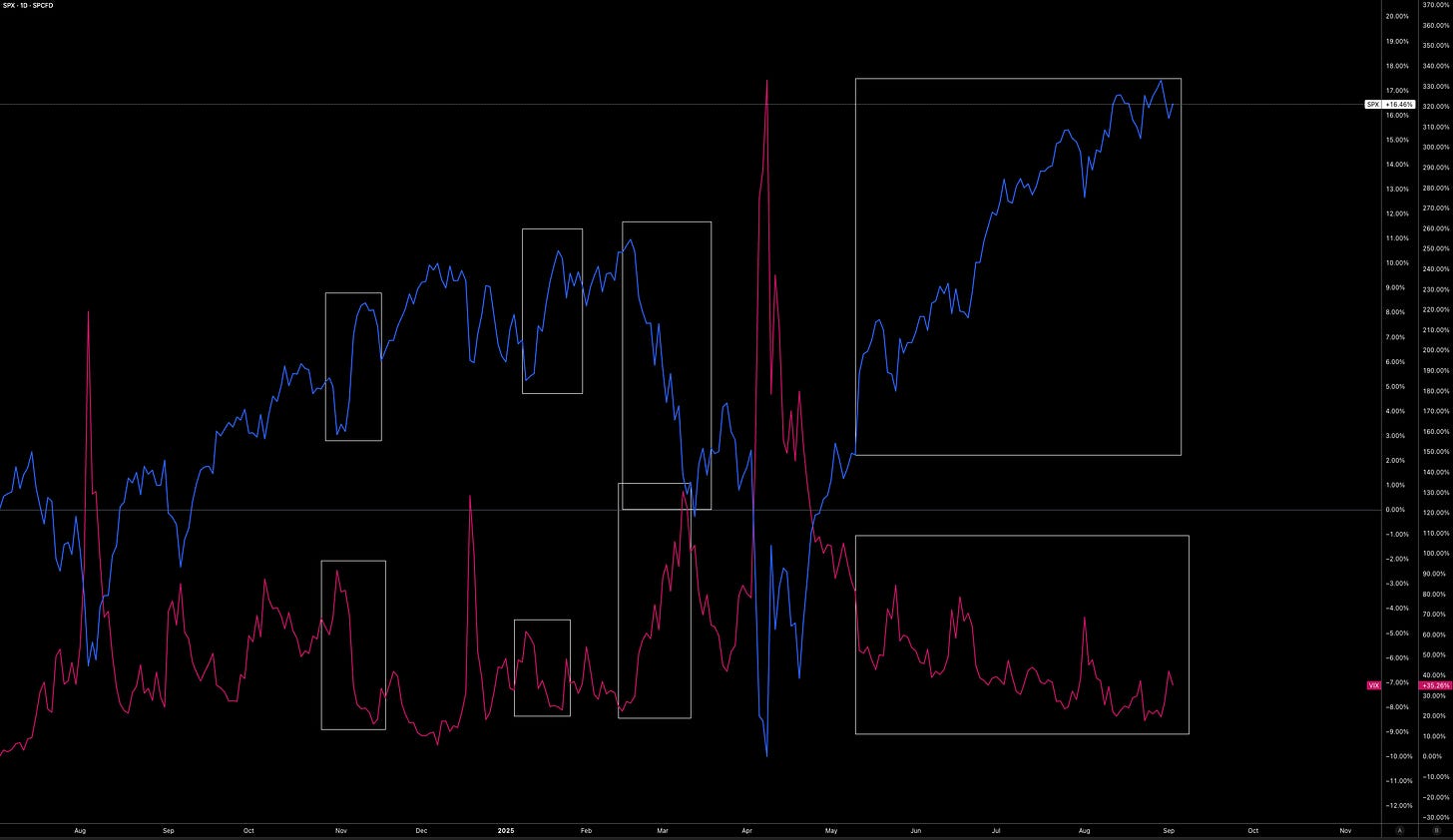

The allure of exotics is that they promise precision in a world of uncertainty. Correlation products, path-dependent payoffs, or hybrid structures can all be engineered to solve very specific problems but at the cost of opacity and operational complexity. They embody the frontier of financial innovation, where creativity meets risk management, and where the line between opportunity and danger is often razor-thin. One way this frontier shows up is in the negative correlation between equities and volatility, as seen in the SPX vs VIX relationship below:

Curve views can be expressed through calendar spreads, butterflies, and packs, while funding efficiency is enhanced through daily margining that avoids bilateral credit agreements.

Calendar Spreads

Buy one futures contract and sell another in the same asset but with different maturities.

Expresses a view on the shape of the forward curve (carry, roll, storage costs, policy expectations).

Example: Long Dec 25 SOFR futures, short Jun 26 is betting the curve steepens between those maturities.

Common in rates, commodities, and FX futures.

Butterflies

Combination of three maturities: long one short-end, short two mid, long one long-end (weights balanced).

Expresses a view on curve curvature (whether the belly is rich or cheap relative to the wings).

Example: Long 2y and 10y, short 2 × 5y, this is a “2s5s10s butterfly.”

Neutral to parallel shifts, but sensitive to twists.

Packs

A block of four consecutive quarterly futures contracts, traded as a unit.

Used to express views on policy over a one year horizon (e.g., Fed rate path).

Example: Buying the 2026 SOFR “pack” = long Mar, Jun, Sep, Dec 26 contracts.

Makes it easy to trade an annualised view without managing multiple legs.

Yet even in their simplicity, futures come with edges and risks: basis and roll dynamics, cheapest-to-deliver mechanics in rates contracts, and shifting liquidity cycles. In practice, funds deploy them as equity beta overlays, duration hedges around macro events, or macro spreads across regions and commodities. The rule of thumb is simple: if the objective is directional exposure or curve shape with minimal slippage, start with futures.

Options: From Linear to Asymmetric

But even the cleanest directional exposure has limits. Futures are linear instruments: they pay off in a straight line, one-for-one with the underlying. When funds need to shape payoffs, hedge tails, or introduce asymmetry, they climb to the next rung: options. Options grant rights rather than obligations, introducing asymmetric payoffs and the full Greek alphabet of sensitivities. This asymmetry is easiest to see in a payoff diagram: unlike futures, where P&L moves linearly with the underlying, options bend the payoff profile into defined shapes

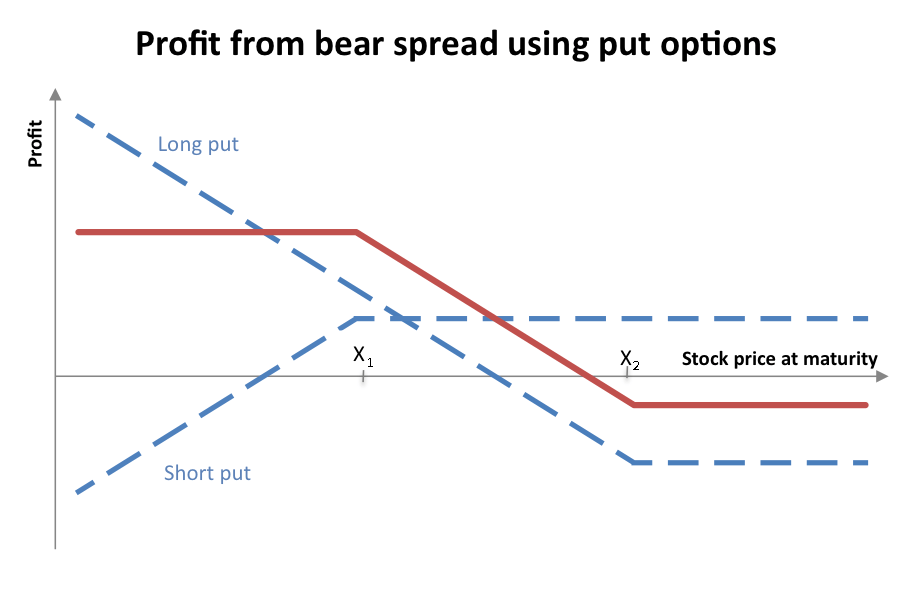

Options are not just instruments, they are blueprints for payoff design. They are used for tail-risk and drawdown control through put spreads or collars, for volatility harvesting via overwriting or dispersion trades, and for payoff shaping that defines floors, caps, and skewed distributions. Structures range from verticals and calendars to risk reversals and butterflies, each tuned to a particular volatility or directional view.

Funds often lean long gamma into events like CPI or payrolls, run convexity sleeves of put spreads financed by call overwrites, or rotate between cheap tail options and rich front-end variance. But options require discipline: path matters, surfaces shift, and liquidity varies dramatically between major indices and far-out-of-the-money strikes. The guiding principle is to reach for options when asymmetry is needed, or when volatility itself is the trade.

Swaps: Precision Overlays and Curve Surgery

As strategies mature, managers often need more precision. This is where swaps enter the picture. These bilateral contracts exchange cash flows, fixed against floating, currency against currency, or credit premia against funding, and are now largely cleared under OIS-based discounting. Swaps allow hedge funds to perform curve surgery by isolating a 2s10s view without the noise of futures basis, to secure foreign funding through cross-currency swaps, or to strip credit exposure through CDS and total return swaps.

Risks in swaps are not measured in notional but in PV01, CS01, and basis sensitivities, with collateral agreements and counterparty terms shaping outcomes even in cleared markets. Hedge-fund applications range from trading swap spreads against Treasuries, to exploiting SOFR-OIS basis, to asset-swapping bonds to isolate credit. Swaps are chosen when precision is required, when listed instruments cannot cleanly capture the curve, credit, or funding dimension at play.

At the very top of the ladder sit exotics and hybrids. These are path-dependent options, variance-linked structures, correlation products, and cross-asset hybrids that allow hedge funds to sculpt payoffs with extraordinary specificity. Payer swaptions provide tail convexity against bond sell-offs, variance swaps let managers isolate realised volatility, dispersion trades monetise correlation risk premia, and range accruals or quanto structures engineer unique exposures to funding or FX.

These instruments are powerful because they unlock convexity and correlation profiles that simply cannot be replicated with vanilla futures or options. Yet they are also dangerous: smile dynamics, hedging gaps, liquidity scarcity, and model dependency all become central. Exotics are not everyday tools but specialist weapons, deployed sparingly by large funds with the infrastructure to manage operational complexity and counterparty interactions.

The decision to climb the ladder requires discipline. A manager must ask: what is the true objective, beta, hedge, tail convexity, relative value, or funding? Does the path of prices matter, or only the endpoint? Is the portfolio willing to bleed carry for convexity, or is the mandate to harvest carry while limiting tail risk? Can the liquidity and governance framework absorb the operational demands of OTC instruments? And, most importantly, is the risk measured in the right units (DV01, Vega, CS01) rather than in misleading notionals that obscure the true exposure?

Case studies illustrate the choice of rung in practice. A 2s10s steepener can be expressed with futures for liquidity and simplicity, or with swaps for precision and fewer basis leaks. An equity drawdown hedge might be structured with put spreads and VIX calls, balancing theta bleed against convex payout. A USDJPY topside bet may combine call spreads with skew monetisation through risk reversals. Inflation driven bond selloff tails can be hedged through payer swaptions, while cross-currency basis normalisation plays sit squarely in the swap space. Each trade highlights the trade-off between liquidity, carry, convexity, and precision, showing how the same view can be expressed in different ways depending on where you stand on the ladder.

The ladder, then, is not a hierarchy of prestige but of tools. The best hedge funds do not climb to exotics for the sake of sophistication, they climb only when the trade demands it. Futures deliver exposure, options deliver asymmetry, swaps deliver precision, and exotics deliver targeted convexity or correlation when nothing else will suffice. The art of derivatives lies not in how far up the ladder you climb, but in knowing exactly which rung fits your objective, and in having the discipline to stop there.

In the end, the ladder isn’t about sophistication, it’s about fit.