Primer: The Hidden Cost of Foreign Exposure

Foreign Capital, FX Hedging, and the Plumbing Behind U.S. Equity Flows

Markets are quiet, which makes this the perfect moment to lay down a primer. I’ve been working tirelessly on new models and analysis infrastructure, as well as the G4 and U.S. dashboards so that I can convert them into full TradingView indicators. Once they’re live, I’ll be able to share far more data and structure through these reports. Plenty more to come in January.

Foreign investors exposed to the S&P this year may have been surprised to see a portion of their strong equity gains eroded by a weaker dollar. That’s worth unpacking, how FX can offset returns, the ways investors manage or hedge that risk, and the conditions under which foreign capital actually starts to leave U.S. markets.

This year has delivered a potent mix which consists of an overly dovish Fed and a Trump administration that has made no secret of its preference for a weaker dollar. Strategically, that stance is understandable. A cheaper currency is a powerful lever in a world of trade wars, supply chain realignment, and ongoing competition with China for global economic dominance.

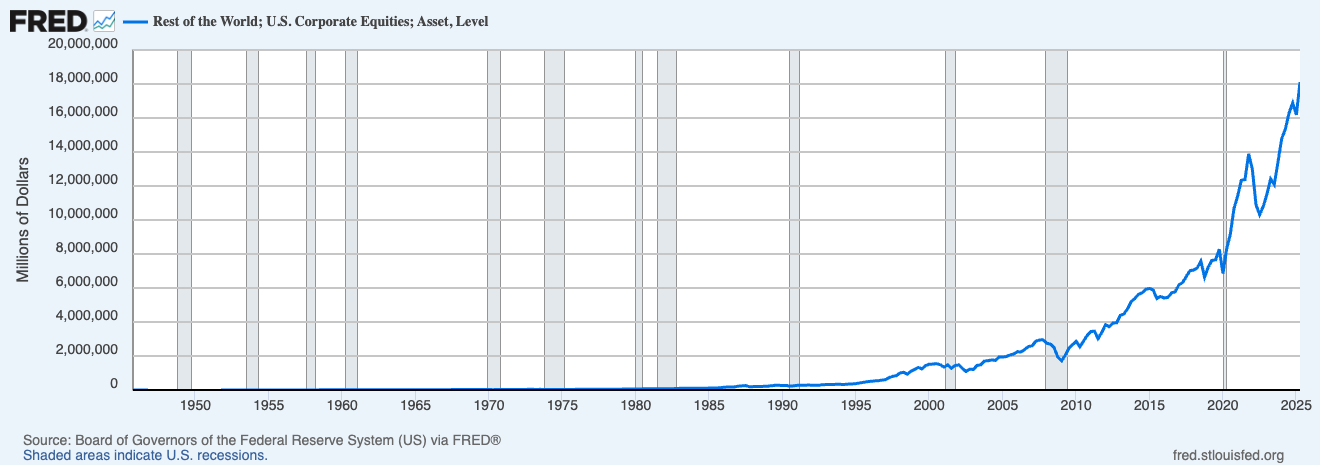

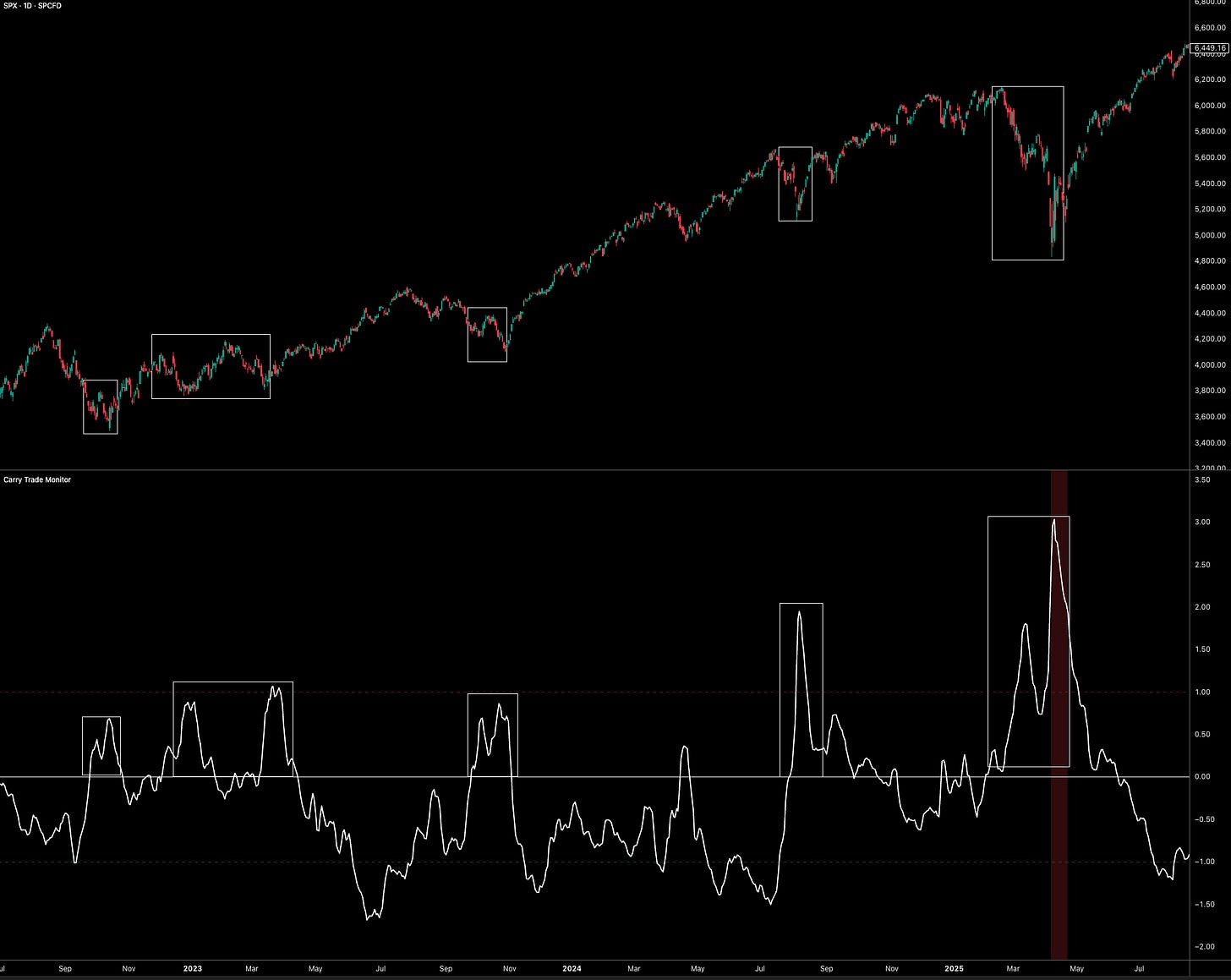

The problem is the side effects. A persistently weaker dollar quietly erodes foreign investors’ U.S. equity returns in home currency terms. And while the U.S. will almost certainly remain a long term destination for foreign capital, there is a threshold beyond which patience wears thin. When the dollar is devaluing at close to double digit rates, U.S. equities must outperform by an increasingly wide margin just to deliver a real, inflation adjusted return. At that point, reallocating or reshoring capital starts being a simple exercise in arithmetic. Just look below how significant a withdrawal of foreign capital can be.

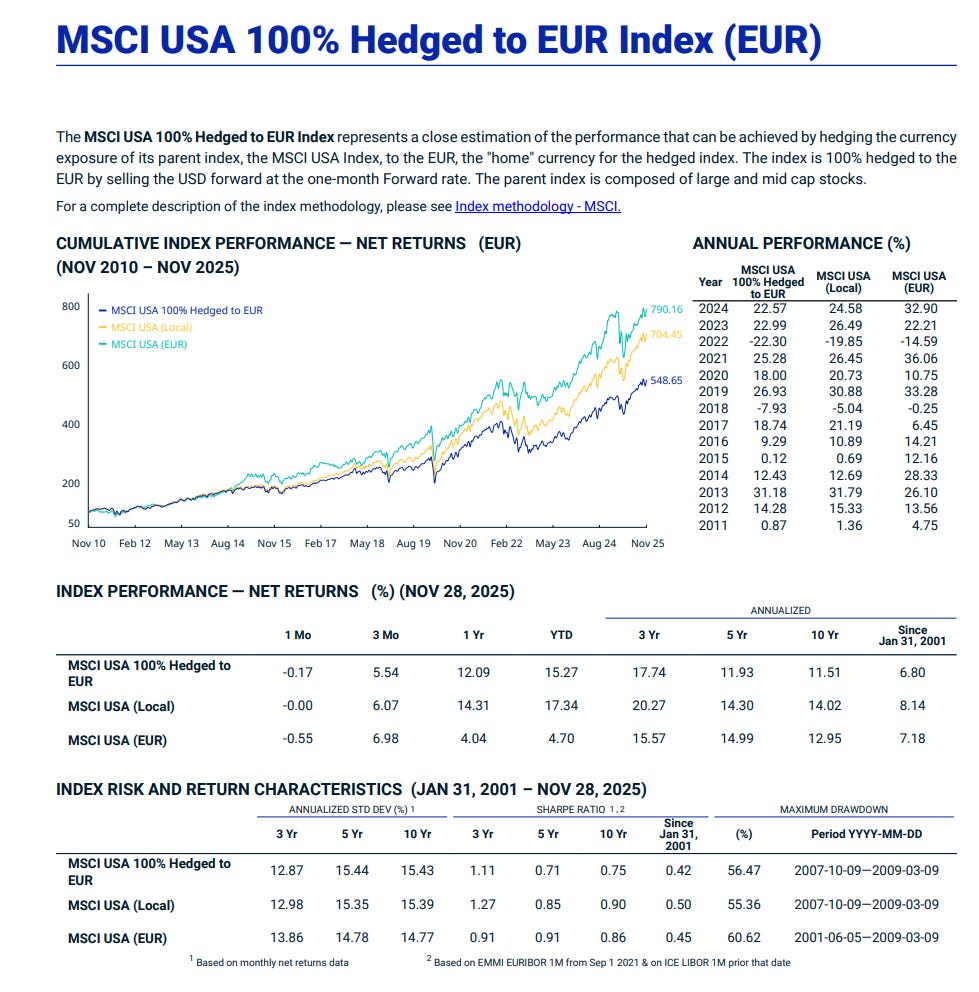

Foreign investment into U.S. equities is usually framed as a vote of confidence, on American growth, innovation, institutions, or all three at once. That story is comforting, simple, and mostly wrong. In practice, foreign ownership of U.S. stocks is far more mechanical, fragile, and conditional. Every foreign buyer of U.S. equities is not making one decision but two: a long position in U.S. risk assets and an implicit long position in the U.S. dollar. Whether that dollar exposure is left untouched, partially neutralised, or aggressively hedged is not a footnote. It reshapes the return profile, the volatility profile, and the portfolio’s sensitivity to global macro shocks. For large institutions, the currency decision can matter just as much as the stock selection itself, and in certain regimes, it completely dominates it. Just look at this below, same stocks… different returns. By no means am I saying that investing dynamics will change immediately, but with more risks in the system, these recent returns could reshore capital.

Once you hedge the currency, U.S. equities stop being a clean growth bet and turn into a bundle of interlocking macro trades. The most common tools, FX forwards and swaps, look straightforward: sell dollars forward against the home currency and move on. But the cost of that hedge is not simply the policy rate gap between the Fed and the ECB or the BOJ. Embedded in the forward price is the cross currency basis, a market signal of balance sheet constraints, dollar funding stress, and how willing global banks are to intermediate the trade. When that basis widens, hedging costs can rise sharply even if headline rate differentials barely move. In those moments, hedging stops being passive risk management and starts behaving like an active macro position with real, sometimes painful, P&L consequences.

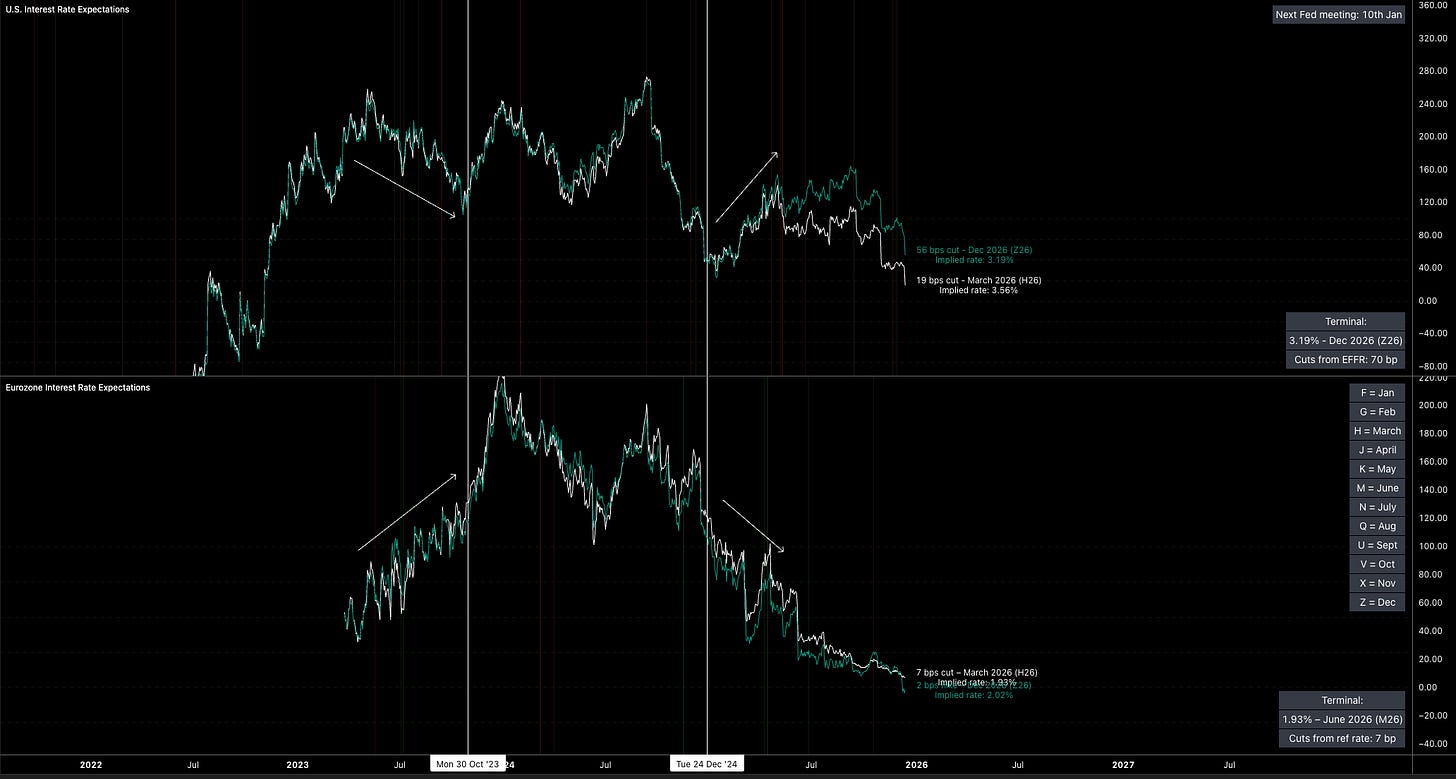

That reality explains why many foreign investors hedge inconsistently, or not at all (much easier for the everyday investor). Some stay largely unhedged because global equity benchmarks are unhedged, and deviating introduces tracking error and, more importantly, career risk. Others lean on a deeply ingrained habit: the belief that the dollar strengthens when global risk sells off, acting as a natural hedge against equity drawdowns. This logic has worked often enough to become institutional muscle memory. But it is brutally regime dependent. When equities fall and the dollar falls alongside them, that natural hedge evaporates, and foreign investors experience a double drawdown in home-currency terms. Those are the moments when FX risk jumps from the appendix to the front page of the investment committee deck. Carry is the entry fee for risk managed exposure to the USD, but when U.S. front ends are high vs Europe, hedging USD back to EUR tends to be costly and is a dynamic we’ve seen espeically with how the rates dynamic across the U.S. has played out this year.

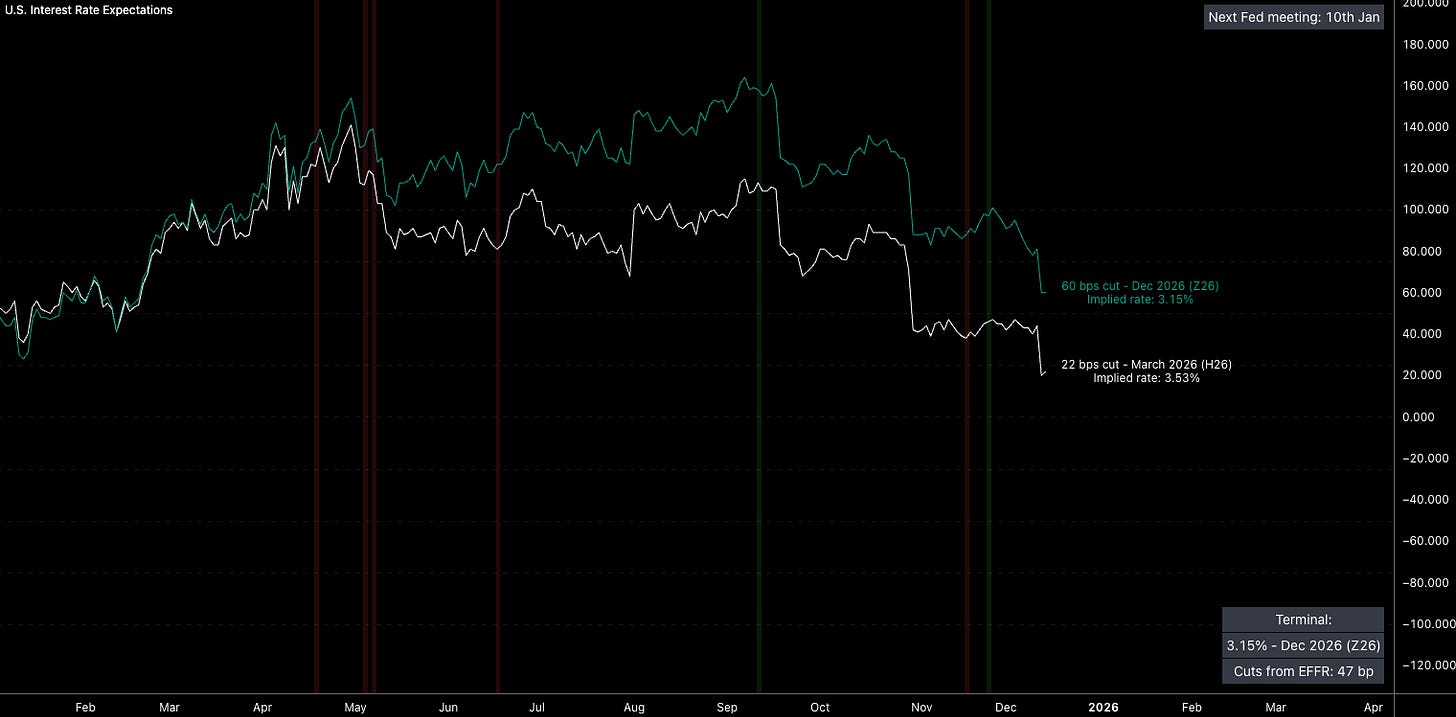

This is why the cost of hedging USD exposure is one of the most important and most underappreciated, drivers of foreign demand for U.S. equities. When U.S. short term rates are high vs Europe or Japan, hedging dollars back into euros or yen can eat a large chunk of equity returns. Foreign investors are then forced into an uncomfortable choice: accept unhedged dollar risk (most common for retail) or reduce exposure altogether. When U.S. rates fall, or are expected to fall, that calculus flips. Hedging becomes cheaper, more predictable, and easier to justify. Ironically, this can lead to heavier hedging that weakens the dollar even as foreign ownership of U.S. equities remains high. Dollar weakness, in other words, does not automatically mean foreigners are selling U.S. assets. Often it simply means they are selling more dollars forward.

Carry is the entry fee for risk-managed exposure to the USD, but when U.S. front-ends are high vs Europe, hedging USD back to EUR tends to be costly and is a dynamic we’ve seen espeically with how the rates dynamic across the U.S. has played out this year. The terminal rate is key here, costs won’t change anytime soon.

At scale, these hedges become macro forces. When large pools of foreign capital hedge equity exposure, the flows run straight through FX forwards, swap markets, and dealer balance sheets. In calm conditions, the system absorbs this quietly. Under stress, the same flows can move exchange rates, widen cross-currency bases, and tighten dollar funding further, creating feedback loops. This is the hedging channel at work: asset allocation decisions spilling directly into FX dynamics. In these regimes, currency moves are less about growth narratives or inflation expectations and more about balance sheet stress and the urgency of risk reduction. Foreign equity exposure is increasing rapidly and is more than large enough that hedging flows can move markets.

Foreign capital tends to pull back from the U.S. when several constraints bind at once. A sudden rise in hedging costs, often driven by a widening XCCY basis or dollar funding stress, is a common catalyst. When hedging becomes expensive or unreliable, reducing the underlying exposure is sometimes the simplest way to reduce risk. Another trigger is the unwind of global carry trades. Many portfolios are implicitly short volatility and dependent on stable funding, even if they are not explicitly borrowing in low yield currencies. When volatility rises and funding tightens, these portfolios behave exactly like leveraged carry trades: risk assets are sold, funding currencies are bought back, and positions are cut quickly and in unison. U.S. equities, deep and liquid, often become the source of that liquidity. Just take a look at the significance of carry trade unwinds, often leads to direct selling of U.S. equities:

Correlation breakdowns add fuel to the fire. When U.S. equities and the dollar fall together, foreign investors face losses that risk models are poorly designed to anticipate. The assumption that USD exposure diversifies global equity risk suddenly looks fragile, prompting uncomfortable structural reassessments. Political and policy risks can amplify this dynamic. Tariffs, sanctions, or perceived threats to institutional credibility introduce tail risks that are difficult (sometimes impossible) to hedge cleanly. When those risks rise, foreign investors may reduce U.S. exposure not because earnings look weak, but because the distribution of outcomes has become unpleasantly skewed. It’s not common, but periods of a falling USD with equities could become more common with the new administration, which can reshore foreign capital fast.

Crucially, foreign exposure does not have to be reduced by selling equities outright. Increasing hedge ratios can achieve a similar reduction in USD risk without touching the asset. To FX markets, selling U.S. equities and selling dollars forward can look remarkably similar. To equity markets, they are very different. This distinction explains why the dollar can weaken sharply while U.S. equities remain resilient, and why equity drawdowns sometimes lag currency moves. The adjustment often starts in the hedge, not in the asset itself.

A clean way to think about foreign participation in U.S. equities is through three interacting state variables. The first is return attraction: earnings growth, innovation, and relative valuations. The second is hedgeability: the cost and stability of currency hedges, driven by rate differentials and cross-currency basis conditions. The third is funding fragility: how levered global portfolios are, how short volatility they are, and how dependent they are on smooth dollar funding. When all three line up, foreign demand is strong and stable. When hedgeability deteriorates and funding fragility rises, even stellar equity returns may not be enough to prevent defensive repositioning. Funding fragility or even a volatility blowout in the U.S. has massive contagion risk for foreigners exposed to equities (especially if it leads to double selling of equities and the USD).

Recent market dynamics fit neatly into this framework. A more dovish Fed and growing confidence in future rate cuts have softened the dollar, reducing expected hedging costs for foreign investors and making higher hedge ratios easier to justify. At the same time, shifting expectations around European policy, less easing, occasional tightening, are narrowing rate differentials and altering the economics of FX forwards, particularly for euro-based investors. These shifts shape the willingness of foreign capital to hold, hedge, or resize U.S. equity exposure. Layer on bouts of EMFX stress, where volatility and funding pressure widen spreads and bases, and the system’s fragility becomes more visible. Hedge costs rise, liquidity thins, and what looked like a benign allocation decision starts to feel conditional.

For macro traders and risk allocators, the lesson is straightforward but often ignored. Tracking foreign flows into U.S. equities is not about obsessing over TIC data or headline equity indices. It requires watching the plumbing (XCCY basis, FX swap pricing, volatility regimes, and the correlation between U.S. assets and the dollar). The most dangerous moments are when they are forced to adjust hedges under stress. Those adjustments move currencies first, tighten funding second, and only later show up in asset prices. Foreign capital rarely exits the U.S. in one dramatic rush. It leaks out through the plumbing long before it walks out the front door.

Have a great weekend!

great post