China: The Balance Sheet Recession

Exploring the fundamental issue with China's economy and why liquidity injections fail to revive consumption.

Hey crew,

Just got back from a walk.

And boy, was it needed.

Had my work playlist running in the back as I disconnected to focus solely on being present.

It’s so easy to be consumed by your thoughts.

One reason why I force myself to get out on a walk from time to time. Let my mind focus on the bigger picture.

Anyways, U.S CPI came in lower than forecasted whilst I was out, 3.2% to be exact, I’ll talk more about that tomorrow.

Today, I want to shed light on the data we’ve seen out of China, and more particularly why we’re not seeing the rebound we thought we would.

China’s Dance With Deflation

The most recent inflation print from China showed prices declined 0.3% YoY in July, the first decrease since February 2021. For an economy whose central bank has pumped stimulus into the economy and reduced headline interest rates such as the LPR (Loan Prime Rate) to 3.55%, deflationary signs are a worry to the central bank and government.

Let’s start from the beginning.

Throughout Covid-19 China enforced some of the strictest measures of lockdown known to mankind. But here’s the thing, whilst countries in the West provided stimulus, benefit programs, social security payments and cash payments directly to consumers, the Chinese government did none of that. Consumers had to weather the storm with little to no support from the Chinese government.

This resulted in Chinese consumers building up a $ 2.6 trillion savings pot throughout 2022. Due to the zero Covid measures, consumers in China weren’t able to journey out to spend their savings on discretionary goods so they could only continue to stack their deposits at local banks. After data came out showing the excess ‘dry powder’ Chinese consumers had built up, meaning cash, everyone rushed to the assumption that consumers would go out and embark on ‘revenge spending’. Insinuating that consumers in China were ready to deploy most of their built-up savings once the economy re-opened, but that wasn’t the case, in fact, it was quite the opposite.

Households and consumers have been reluctant to spend, choosing to pay off debts and continue building up their safety net which has put a massive hole in Chinese consumption data.

I know what you’re probably thinking, but isn’t China’s economy built more so on exports than consumption?

Not any more.

China’s strategic plan and main priority are to eliminate its dependence on foreign countries for technological goods but also, limit its economic dependence on exports.

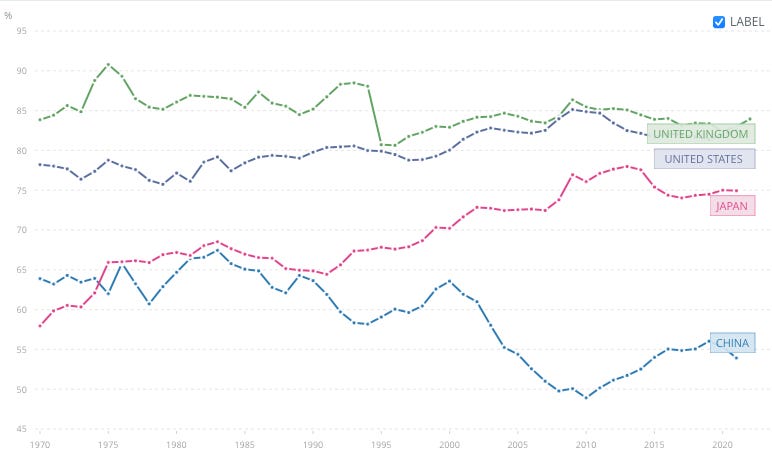

Take a look at Chinese consumption as a share of GDP.

This chart shows the dependence each economy has on its domestic consumption to drive GDP, and as you can see, China’s economy lags behind its global peers. Hence why policymakers have made it their priority to boost consumption within the country, but when you have a consumer population experiencing something we would quote called a ‘balance sheet recession’ named by Richard Koo, Chief Economist at Nomura Research Institute, reviving consumer spending isn’t an easy task.

Here’s how Richard Koo explains what a balance sheet recession is:

“The ‘balance sheet recession’ is triggered by the notion that people feel uncomfortable about their balance sheets, they believe their debt is too large relative to their assets, and that typically happens after the bursting of a bubble. If the bubble is financed by debt, and asset prices collapse but the liabilities remain, people then realise that their balance sheet (financial position) is under water. Then consumers turn their focus on fixing this ‘balance sheet’ problem by spending down debt.”

Richard Koo, Chief Economist at Nomura Research Institute

Now I hope you can start to see why the PBOC cutting interest rates is having no effect on consumer activity, or inflation, whether interest rates are higher or lower, consumers aren’t interested in taking loans adding more debt to their balance sheet (financial position). They are only focused on bringing their debt levels down.

Now this is fine on an individual level, but when everyone within an economy does this at the same time, that’s when the real problem occurs.

Let me explain.

Credit is the creation of new money in the economy. Now when a consumer pays down debts or repays loans, they’re doing the exact opposite of credit, so this process destroys the money supply within the economy. The issue with China is that this is happening on a large scale, the ‘bubble’ in this story is the residential real estate market which is on a steep decline from all perspectives as we’ve actively seen over the past 2 years with large defaults looming over some of the largest property developers in China with prospects for more Evergrande-like crisis.

If you were wondering what the reference was, Evergrande is the second largest property developer in China, but that’s not what they were known for, with over $300bn in liabilities the development group defaulted on over $20bn of international bonds.

Let’s break down this chart above. The LHS index shows the real estate climate index, a reading above 100 suggests a prosperous housing market and a reading below suggests the opposite. The RHS axis shows the investment completed by enterprises for real estate development YoY, which has steadily declined over the past two decades to -7.90%.

Let me make the importance much more significant to you.

After testing out a few theories, notice how real estate development has a 0.66 correlation coefficient with Chinese GDP, the scale is -1 to 1.

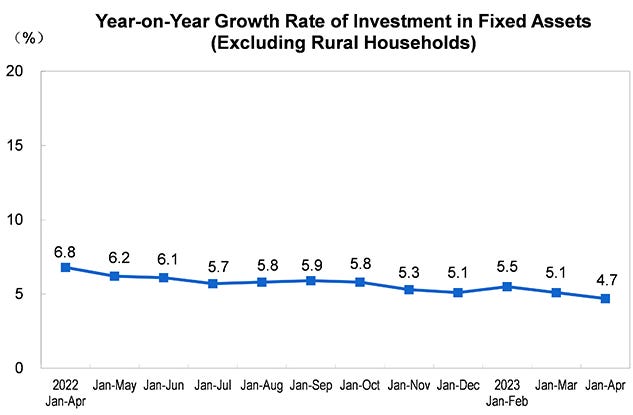

The closer the figure is to 1, the greater the correlation to Chinese GDP. Not only that but actually completed fixed asset investment leads Chinese GDP by a whole quarter, so looking at where fixed asset investment is now we can expect Chinese GDP to also slow towards the end of 2023 leading into 2024.

The total investment for real estate development accounts for 20% of fixed asset investment, so now we can understand why the FAI (fixed asset investment) data from China has been declining.

This leads us perfectly to the performance of the Yuan.

The CNY has been one of the worst-performing Asian currencies, with state and commercial banks continuing their spree of selling dollars in the offshore market in order to artificially prop up the Yuan. The PBOC still continues with its daily fixing of the Yuan, setting the midpoint and the +/- 2% band it can trade within but with the widening interest rate differential between China and U.S, investors selling out of Chinese bonds, a further crackdown on the private sector and weak economic growth capital has flown out of the country to the likes of the U.S where risk-free yields are c.4.00%(US10Y) and other capital fleeing to Asia’s ‘Switzerland’ Singapore.

This is the rate differential between the US10Y and CN10Y.

US10Y (4.094%) - CN10Y (2.656%) = 1.438%

Add to that you wouldn’t have to worry about liquidity issues in the U.S Treasury market or random unaccounted risks.

Which would you choose? That’s right U.S Treasuries all day.

All of these things have aided investment away from the nation and the economy into deflation, now remember that in a deflationary environment, debt becomes more expensive to finance, both for households and for governments, so this mounts pressure on the private and public sectors in China.

IMF forecasts headline growth will expand by 5.2% in 2023 followed by a 4.5% expansion in 2024.

In my opinion, the real factor of whether we see China pull out of a deflationary environment and kick its industrial and export business up is dependent on how heavily the PBOC intervene in markets in order to force the mechanism of the Chinese economy to turn.

Hey guys, firstly thanks for reading until the end.

I wanted to cover commodities and commodity currencies but truth be told, I would have had to leave out a lot of important data and facts so I’ll dedicate next week’s report solely to that.

I hope you enjoyed it and took away some key information.

Until next time,